Singapore’s public housing policy is one of the most dynamic and closely watched in the world. From the way Housing & Development Board (HDB) flats are allocated, to the schemes available for Executive Condominiums (ECs), adjustments to eligibility criteria often spark intense public debate.

In an opinion piece published by The Business Times, writer Leslie Yee argued that it is time to raise the income ceilings for new HDB flats and ECs, noting that the last revision was almost six years ago. Yee also proposed that future increases should be done in fixed amounts at pre-determined intervals, such as every two years, to provide greater predictability for homebuyers.

Based on the points raised in that article, we agree with much of the reasoning — but also see areas where the proposal could be refined. Here’s our take.

Why Raising the Income Ceiling Makes Sense Now

Singapore last adjusted the income ceilings for public housing in September 2019. At that point, the monthly household income cap for new HDB flats was raised from $12,000 to $14,000, while the EC cap moved from $14,000 to $16,000. Those changes reflected both rising incomes and the desire to keep HDB and EC options accessible to middle-income households.

Fast-forward to today, and the economic landscape has shifted noticeably. According to official statistics cited in the Business Times piece, the median monthly household income (including employer CPF contributions) rose nearly 20% between 2019 and 2024, from $9,425 to $11,297. That translates to a compound annual growth rate of 3.7% — well above the inflation rate in some years.

Meanwhile, housing supply conditions have also changed. HDB plans to launch 55,000 BTO flats between 2025 and 2027, and the EC supply in 2025 is projected to be the highest in over a decade. In the past, high demand and limited supply made ceiling adjustments a rather sensitive topic, as they risked flooding the market with new eligible buyers. But with increased supply on the horizon, the window for an upward revision is arguably more favourable.

For households at the upper end of the middle-income bracket, stagnant ceilings risk pricing them out of the most affordable segment of the market. These are not necessarily the ultra-wealthy — they are often dual-income professional couples whose earnings have risen naturally with career progression, but whose housing choices have narrowed due to private market prices rising faster than incomes.

The Appeal of Predictable, Fixed-Interval Increases

Yee’s most notable proposal is to raise the income ceilings in fixed amounts at pre-determined intervals — for example, $1,000 for HDB flats and $1,500 for ECs every two years. This would mark a shift from the current approach, where revisions happen irregularly and often after significant market pressure has built up.

The advantages are clear:

1. Better Planning for Homebuyers

Couples could plan their housing moves more strategically if they know when and by how much income ceilings will rise. This reduces the “guesswork” and stress that currently lead some to make hasty resale purchases or, conversely, to wait too long and miss their eligibility window.

2. Smoother Demand Patterns

Incremental, predictable increases would avoid the demand spikes that often follow sudden, large adjustments. When ceilings are raised abruptly, there is typically a surge of newly eligible buyers rushing into the next BTO or EC launch, pushing up competition and application rates.

3. Alignment with Wage Growth

Fixed-interval increases can be calibrated to track average income growth, ensuring eligibility criteria remain relevant without waiting for a multi-year catch-up.

Where the Proposal Needs Careful Calibration

While the logic for higher ceilings is sound, the execution requires caution. Raising eligibility without safeguards could create unintended consequences, particularly for lower-income buyers.

The Risk of Crowding Out

Raising the ceilings allows higher-income households — who often have more resources, better financing options, and greater flexibility — to compete for the same limited pool of new flats. This can make it harder for lower-income households to secure units in well-located projects, especially in mature estates.

Possible safeguard: Maintain priority quotas for households below certain income thresholds. This could take the form of a reserved portion of flats in each BTO launch for applicants earning, say, under $8,000 or $10,000 per month. Such targeted measures would preserve access for those with the greatest financial need.

Demand Concentration in Prime Locations

Even with steady supply, certain launches — especially those categorised as Prime flats — will attract disproportionate interest. If ceiling hikes coincide with the release of high-demand sites, the result could be intense competition and higher application rates in those specific projects.

Possible safeguard: Retain flexibility in the fixed-interval model to pause or moderate increases if market conditions tighten unexpectedly. Predictability is useful, but rigidity could backfire if it fails to account for supply-demand shocks.

Affordability Beyond Eligibility

Eligibility is not the same as affordability. Being allowed to buy a $768,000 4-room PLH flat does not mean a household earning $16,000 a month can comfortably finance it, especially if interest rates remain elevated. Similarly, a $1.7 million EC might technically be within reach for a couple earning $19,000 a month, but the mortgage burden could be significant.

Possible safeguard: Singapore already tapers housing grants based on household income — for example, the Enhanced CPF Housing Grant for BTOs and resales phases out entirely at the $9,000 income mark, and EC grants end above $12,000. If income ceilings are raised, policymakers could consider tightening this taper further or lowering the income threshold where grants phase out. This would ensure that newly eligible, higher-income households do not receive the same level of subsidy as middle-income buyers, keeping public resources more targeted while still allowing broader participation.

The Broader Policy Question: What Role Should HDB and ECs Play for Higher-Income Households?

The debate over income ceilings ultimately comes down to a philosophical question: should public housing cater only to those with no other viable housing options, or should it remain a broadly accessible choice for most Singaporeans, regardless of income?

Singapore has long taken the latter approach, with home ownership seen as a cornerstone of social stability and nation-building. But as incomes diversify and private housing prices surge, the definition of “affordable” is evolving. For some, the appeal of a new BTO or EC is not just the lower price compared to private property, but the stability, quality, and community that come with public housing.

If policymakers decide to keep higher-income households within the HDB/EC framework, ceiling adjustments must be paired with measures to protect access for lower-income buyers. If, instead, they choose to focus on the lower and middle tiers, ceiling hikes should be modest and carefully monitored.

A Calibrated Path Forward

In essence, we share the core view expressed in the Business Times piece: raising the income ceilings now is justified, and introducing a predictable schedule for future increases could improve market efficiency and buyer planning.

But our “two cents” is that policy changes of this magnitude should not be applied uniformly without guardrails. The housing market is not a static system — it is sensitive to supply cycles, economic shifts, and policy interplay.

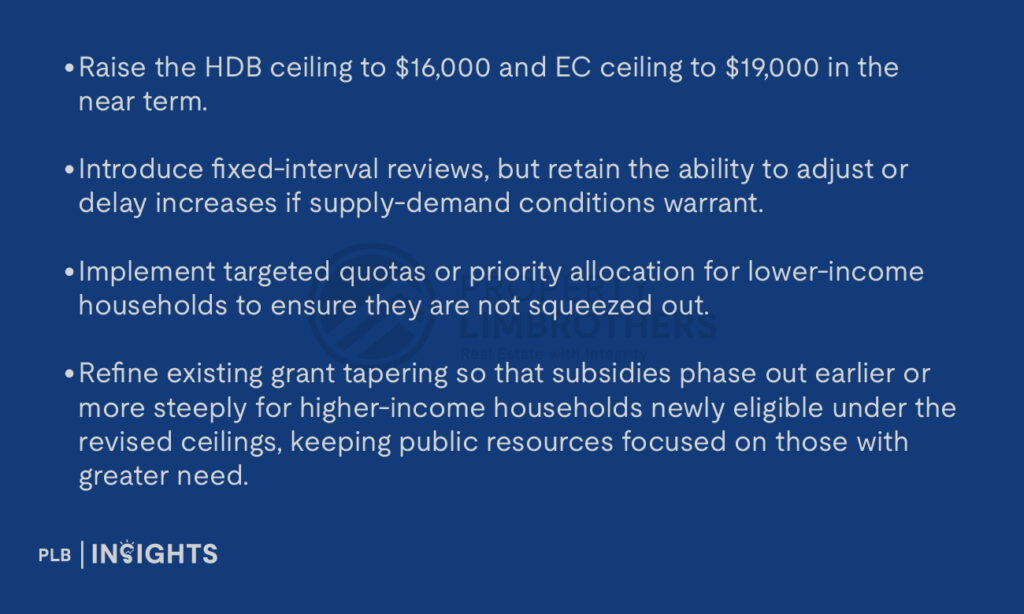

A measured approach could look like this:

Conclusion: Raising Ceilings is the Easy Part — Managing the Impact is the Real Work

Raising income ceilings for HDB and EC buyers may seem like a straightforward policy tweak, but it has ripple effects across the housing market. Done right, it can keep public housing relevant, improve planning for buyers, and smooth market demand. Done without safeguards, it risks intensifying competition and eroding affordability for those who need it most.

As with all housing policy in Singapore, the devil is in the details. The right balance between inclusivity and protection for vulnerable segments will determine whether higher ceilings strengthen the public housing system or strain it. Nevertheless, whatever policymakers decide to do, we have utmost confidence that the next policy change will ultimately benefit Singaporeans — as has been consistently proven over the decades.

Wondering how possible policy changes may affect you? Speak to our sales consultants and plan your next move with confidence.